Cups of nun chai

2010-2020 (and ongoing)

The sharing of pain is one of the essential preconditions for a refinding of dignity and hope. Much pain is unshareable. But the will to share pain is shareable. And from that inevitably inadequate sharing comes a resistance.

John Berger, The Shape of a Pocket

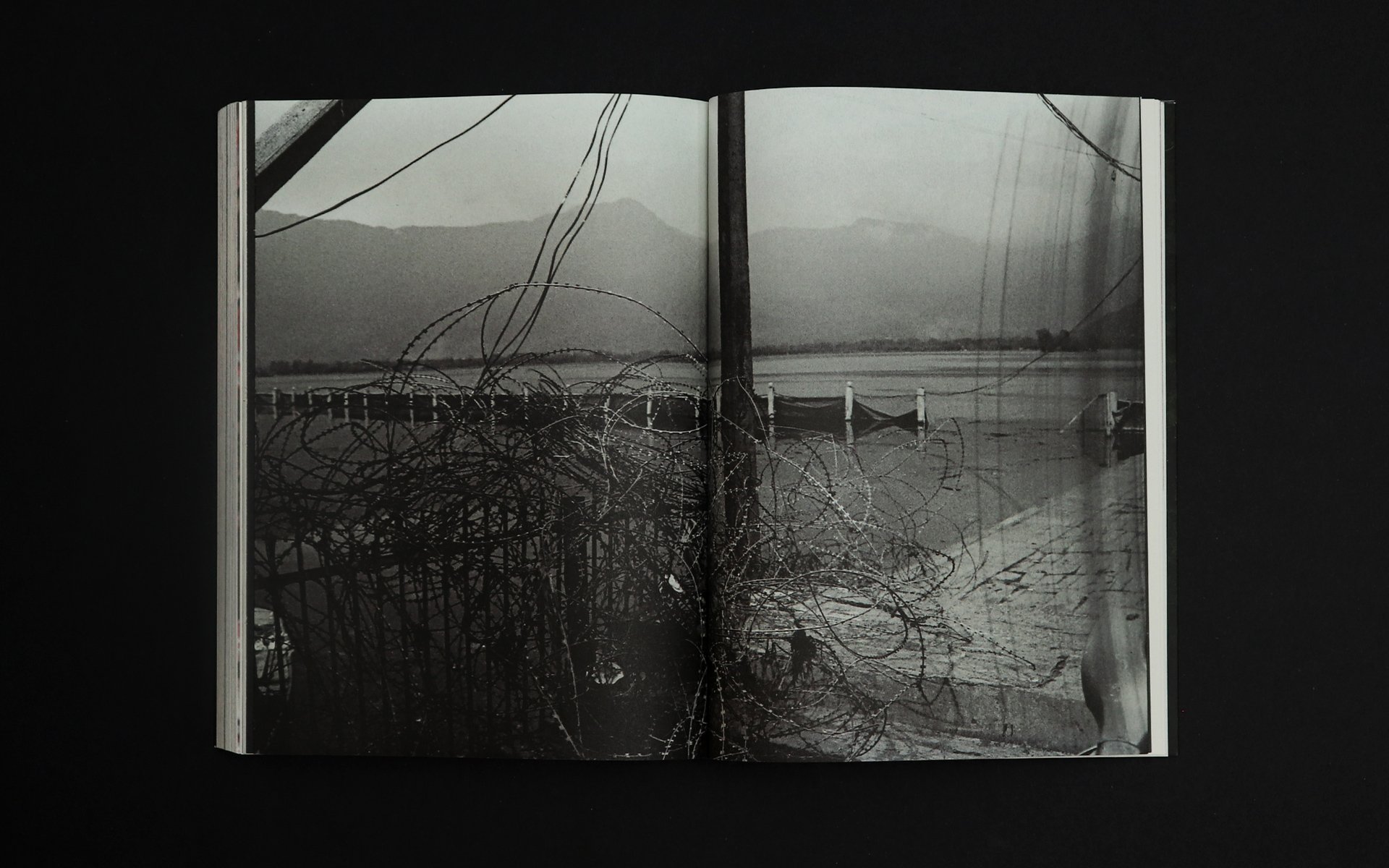

Adroit, and shot through with an extraordinary, even stubborn, compassion, Cups of nun chai reflects on Kashmir, but also on nation-making and colonisation, and on power and violence. The histories, political forces and grief behind this work emerge gradually, but with great sensitivity. And eventually with an unexpected degree of ferocity.

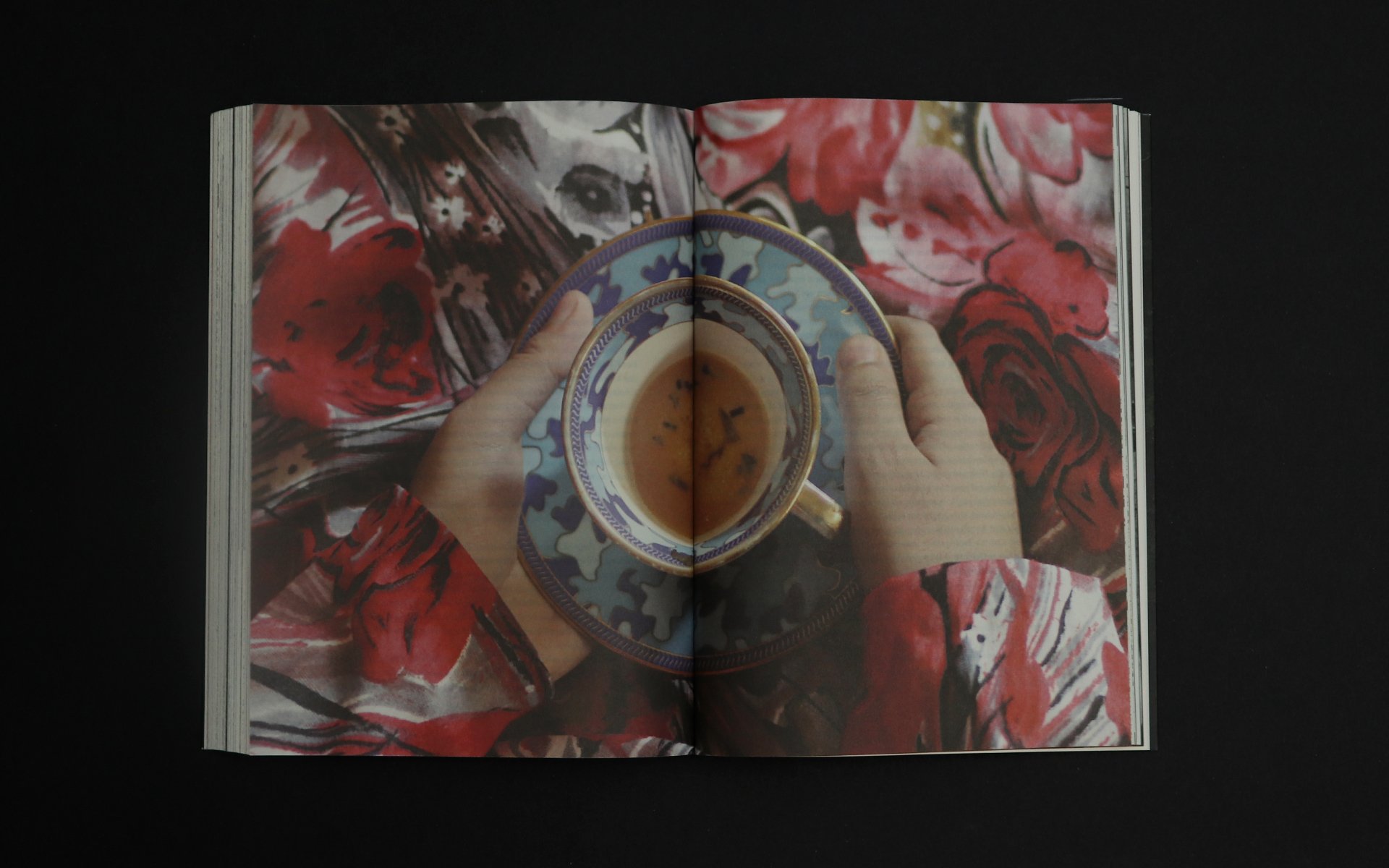

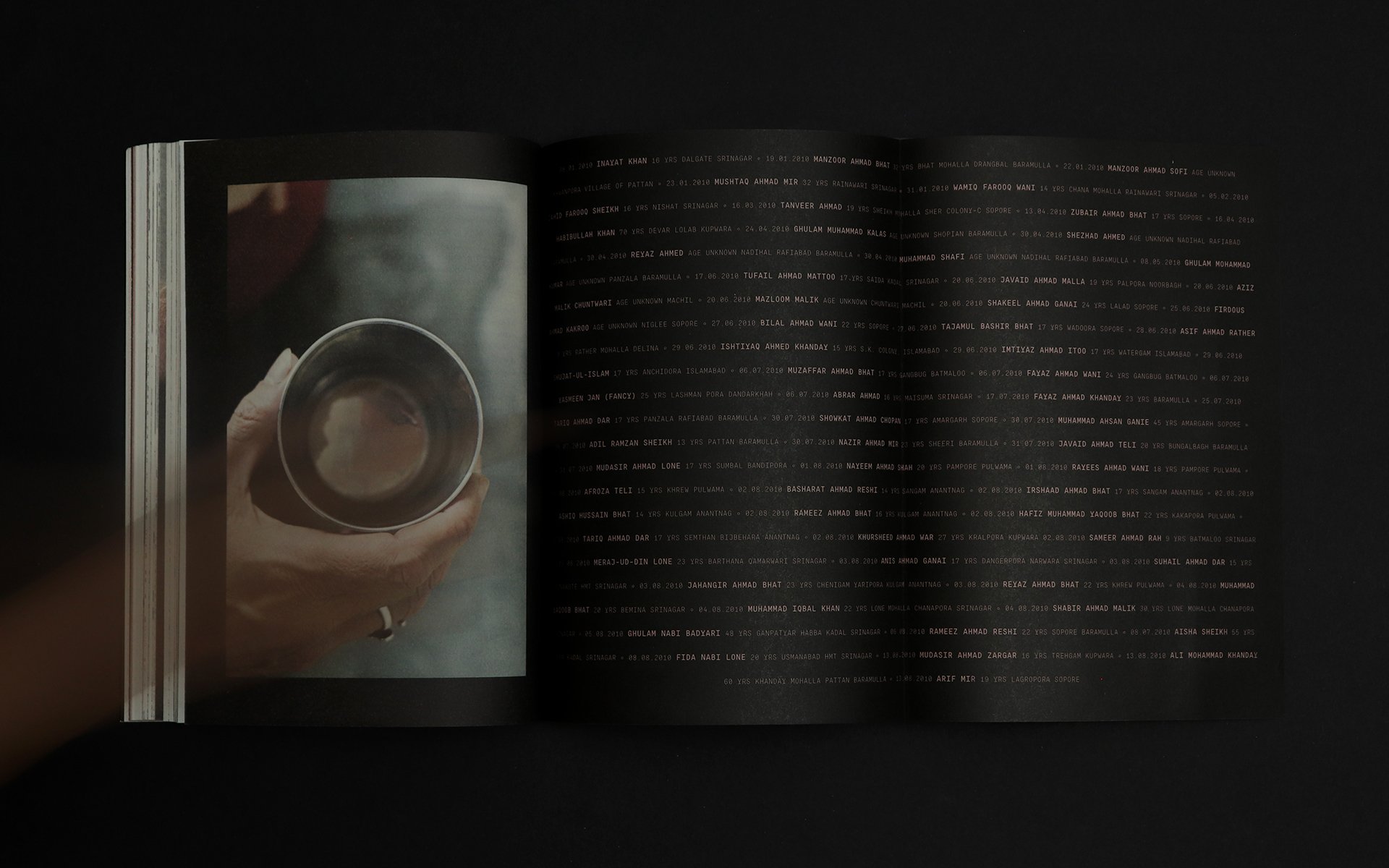

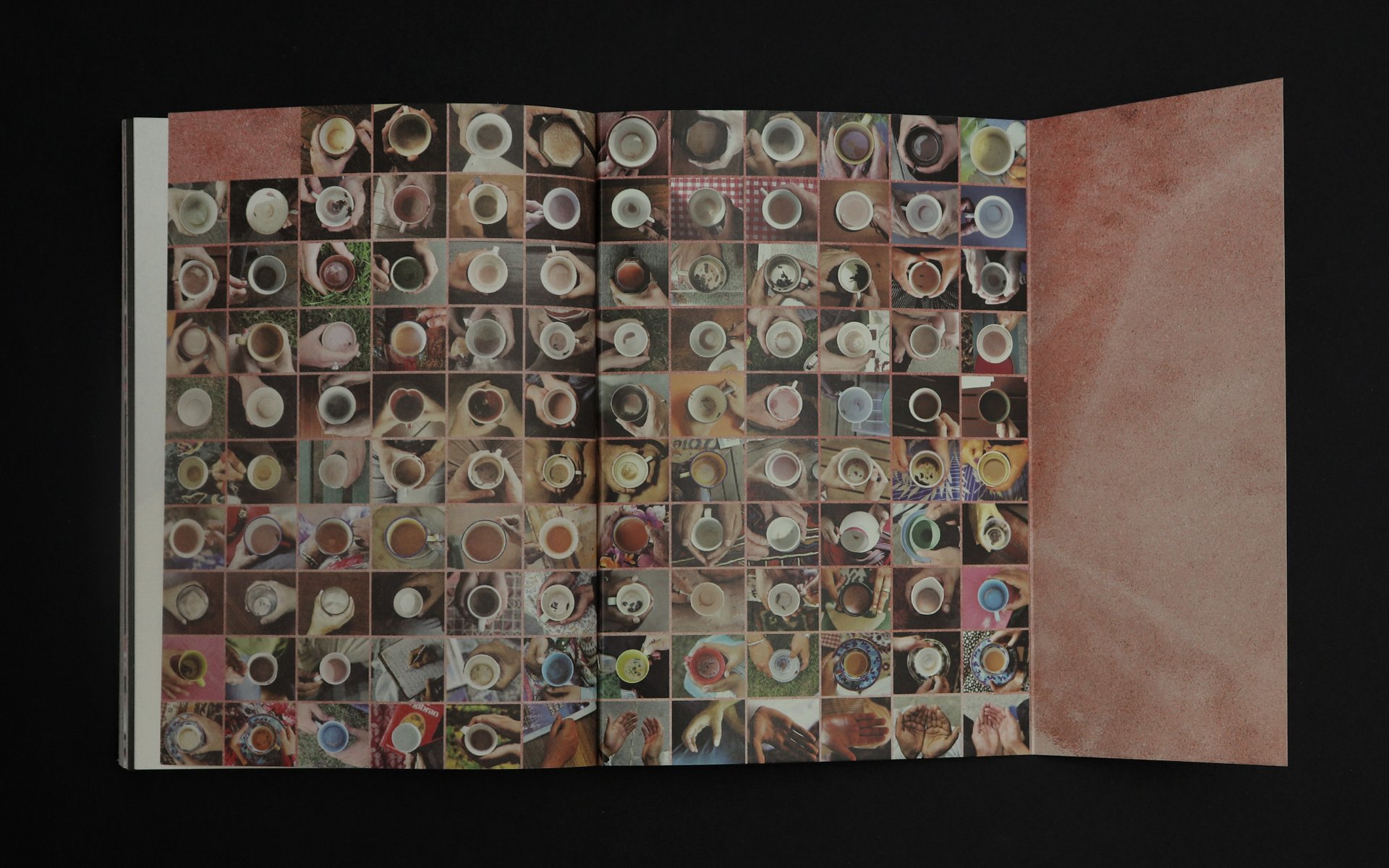

Like an ever-growing memory, Cups of nun chai is a decade long evolving body of work that records the sharing of one hundred and eighteen cups of nun chai, and just as many conversations. Each cup formed a requiem for one hundred and eighteen people killed by the state amidst pro-freedom protests that shook the Kashmir valley during the summer of 2010.

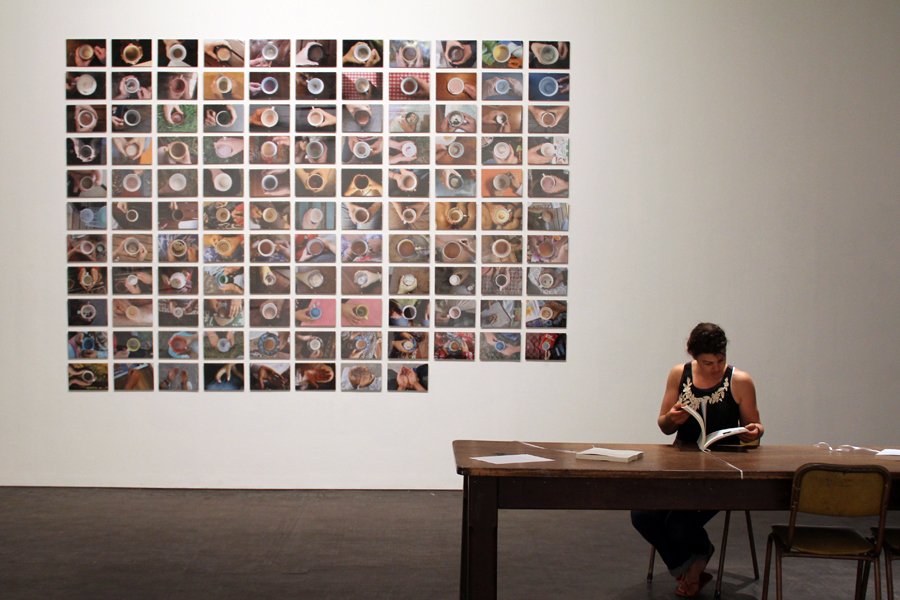

The work unfolded over two years of tea and conversations, accumulated on a website, appeared in occasional exhibitions, and throughout 2016-17 was serialised in 86 editions of the Srinagar based newspaper Kashmir Reader. In October 2016 Kashmir Reader was banned for 3 months amidst a government crackdown on civil society following the assassination of a popular rebel commander.

In 2020 New Delhi based Yaarbal Books published the work in book form to critical acclaim with reviews in Third Text, New Left Review, Hyperallergic, among many others. The book was reprinted in 2021 and continues to circulate in regular book stores, exhibitions and events.

Visit the full work at www.cupsofnunchai.com

Cups of nun chai is a search for meaning in the face of something so brutal it appears absurd. It is an absurd gesture when meaning itself becomes too much to bear. It is also a memorial, grounded in the killing of 118 civilians during protests that roiled Indian-controlled Kashmir during the summer of 2010.

This work is born out of a juncture that is as personal as it is political, as geographically and culturally dislocated as it is grounded.

Cups of nun chai unfolded over two years of tea and conversation with 118 people, most of them in Australia, some in India and finally back in Kashmir. There were no rules, so long as each person understood their cup of nun chai formed one part of a growing memorial for those who were killed during the summer of 2010 in Kashmir.

Navigating the time and space crafted by these cups of tea—at times with complete strangers—each conversation drew on the specific individual, and on its specific location, tracing connections with Kashmir across the shared global heritage of colonial violence, and particularly within South Asia and Australia. Also, and most importantly, forms of resistance to it—from political coups and mass mobilization, to poetry, rap music and journalism, to the vitality of the domestic sphere, and the power of dreams and gesture.

Each cup of tea was photographed and each conversation written about from memory, and these images and words accumulated progressively online, and occasionally in exhibitions. In June 2016, on the anniversary of Tufail Ahmad Mattoo’s killing, Cups of nun chai began to circulate in the Srinagar-based newspaper Kashmir Reader. Like an undercover exhibition slipping within the folds of a newspaper, reaching tens of thousands of people each week over a period of eleven months.

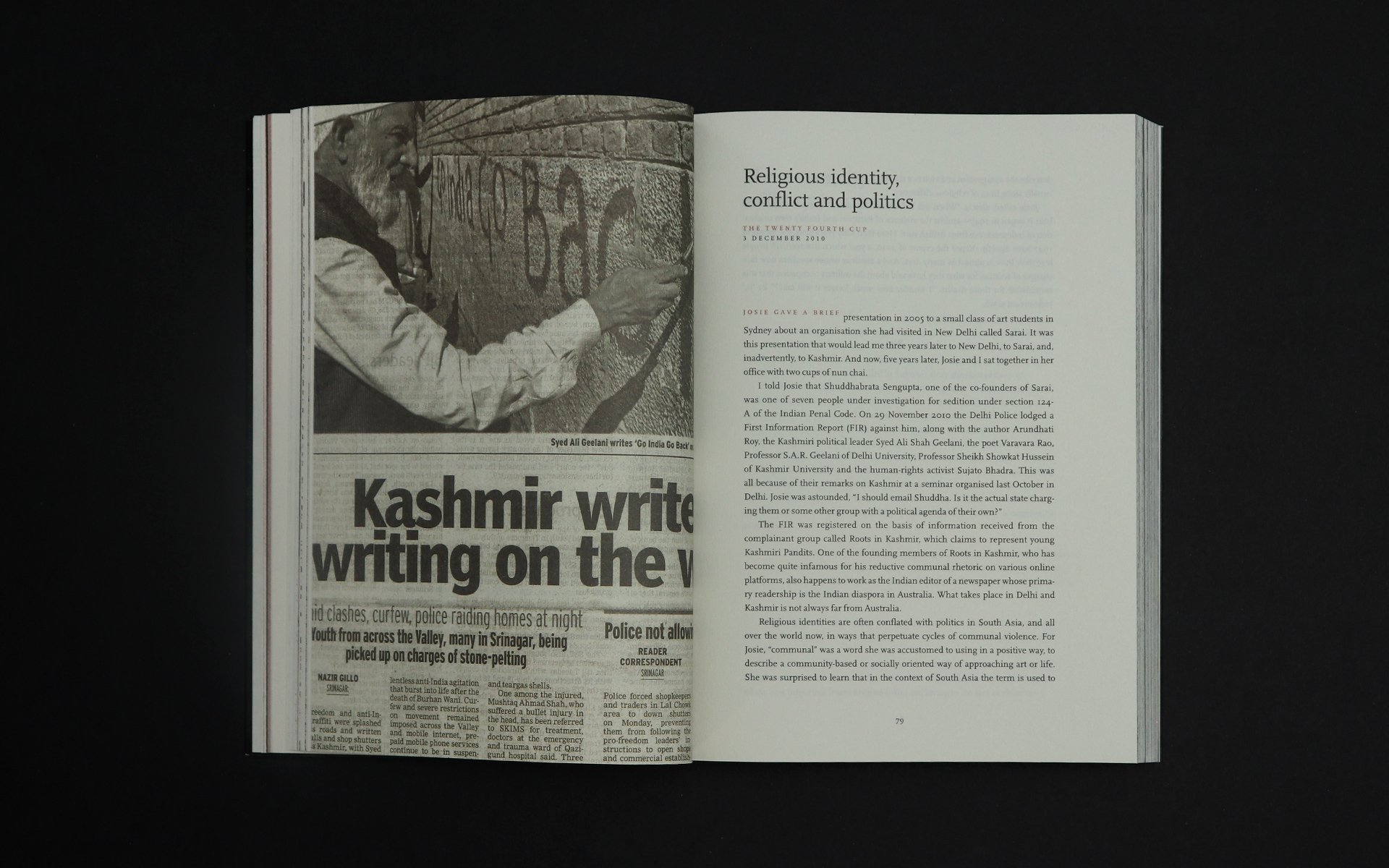

Amidst a renewed government crackdown on civil society following the killing of the popular rebel commander Burhan Wani, Kashmir Reader was banned in October 2016 and remained out of circulation for three uncertain months. The newspaper ban is just one of the many and ongoing pressures the Indian state exerts on Kashmir’s fragile, yet determined, media fraternity. When the newspaper ban was lifted, the serialisation of Cups of nun chai continued. In this space Cups of nun chai found itself published amid daily news in the pages of Kashmir Reader, as the events of 2016-17 collided with the memory of 2010, blurring the formal lines between art work and historical document.

Like an ever growing memory, Cups of nun chai has brewed into various iterations; tea, conversation, website, newspaper serial, exhibition, archive, reading and discussions, that have circulated through exhibitions and events in Australia, in the United States, in Indonesia, in Kashmir, India and Pakistan.

In late 2020 Cups of nun chai was published in book form by Yaarbal Books, New Delhi. The book is available online and at many good bookstores.

Reviews

(for a more complete list of related media, exhibitions and events please visit: www.cupsofnunchai.com)

The contemplative pace, readerly cadence and conversational manner of the book allows one an immersive and extensive understanding of the valley through 118 interactions which recount its political shifts and histories over broad spans of time. Interacting with those who have had some exposure to the region, it asks us to think about how the news and media have conditioned our memories and approaches to places, but often misled us. However, through this act of memorialisation and recollection, the place of Kashmir becomes once again, a living concern. The very ethics of the narrative voice, of disclosure, makes us realise that Kashmir is an atlas for protests everywhere, making us further aware about how ‘positions’ are subconsciously, and sometimes stridently taken in an increasingly self-aware world. / FAST FORWARD

The(se) conversations, sprinkled with flecks of memory like the pieces of a broken mirror, illuminate a myriad of representations, against the illusory facade of a coherent singular narrative. Memory as a methodological tool as used by Hunt to approach the complexity of the situation in the region is not to be confused with nostalgic lamentation for the past or an act of mystic introspection. Rather, in the face of the state’s official claims of a peaceful situation in the region, as well as the wilful amnesia of previous state-sanctioned atrocities, individual memory functions as a tool of defiance against the logic of teleology to recognise the ruptures in the social fabric. / THIRD TEXT

The book defies easy categorisation. Its physical size and engagement with language resemble those of a novel, but it carries an artwork within its pages. However, it does not carry the weight or preciousness of an art object or a photo book, allowing it to travel more freely among readers. It is this cusp of the form, which would allow the book to “sit in the politics or history section of a book shop as much as the art or photo section,” that Hunt wanted to explore…The consistent subversion in the form, as well as the language—visual and textual—that we use to define violence, is at the core of the work. It is this re-imagination that can challenge how a place has been “seen,” and thus offer new possibilities to imagine its freedoms. / THE CARAVAN

Tea-drinking as an act of witness? The conceit is less naïve than it is seems. Like the Parisians clueless of Algeria in Chris Marker’s La Joli Mai (1962), most of Hunt’s interviewees know next to nothing about Kashmir, which, paradoxically, makes for fruitful dialogue. They ask common sensical questions (…) that she patiently answers, filing in the historical and political background, offering a useful primer on the occupation. Their more wide-eyed observations – ‘When people are mourning, they are being killed!’; ‘They are killing children!’ – carry a simple moral force, burning through the justifications of the Indian state. The discussions also fill a void in the cultural discourse on Kashmir, which tends to be presented in the media as a conflict zone and nothing more. / NEW LEFT REVIEW

Throughout Cups of nun chai, Hunt repeats one fact—“over 70,000 people have been killed since the armed rebellion broke out in Kashmir in 1989.” This bare truth about Kashmir should haunt us. Killing of children as small as eight-year-olds is not only a blemish on our collective consciousnesses but an ugly blot on the canvas of civilisation we so proudly claim ourselves to be. When brutality is screamed from rooftops, it becomes a “normality”. Hunt reveals this normality not by screaming but by quietly whispering in our ears like a mother comforting a dying child…This masterpiece by Hunt needs to be read urgently, not for understanding the common Kashmiri but for understanding ourselves and our persistence with the narrative of jingoism, hate and violence. / INDIAN EXPRESS